The Norman churches: Thousands arose stone-by-stone across a conquered land

Scholars may debate the socio-cultural implications, but there’s no doubt that the English landscape changed dramatically during the high middle ages. Over hill and over dale, Norman churches, cathedrals, and castles imposed massive, immovable, yet beautifully delicate structures across bucolic scenes. But would they stand the test of time?

Norman churches of England: Their place in the history of a new nation

Story by Andrew Hatcher

Photography by Lionel Wall and Matthew Slade

As any English schoolboy or girl will tell you, 1066 is the year of the Battle of Hastings and the Norman Conquest, a date that for centuries has been central to the history of the nation.

It is true that a unified England of sorts had been pulled together in the years after the Romans left in AD410, and we see the early movement toward a united nation under Anglo-Saxons kings such as Alfred the Great and his immediate descendants.

It is true that a unified England of sorts had been pulled together in the years after the Romans left in AD410, and we see the early movement toward a united nation under Anglo-Saxons kings such as Alfred the Great and his immediate descendants.

And certainly, this island story would not be complete without mention of the unity that was brought by the mission of St Augustine in AD597 that brought Christianity to the British Isles.

But these early efforts at nationhood lacked a sense of solidity and permanence and were prone to the invasions of the feared Vikings.

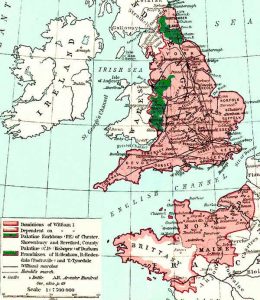

So it is to 1066 and the arrival of the Normans, portended so clearly when Haley’s Comet flashed across the night sky in the early part of the year, that the English look to when telling of the origins of their national story, and if there is to be a figure at the centre of this, it would have to be England’s first Norman king, William the Conqueror, the Duke of Normandy

Who were the Normans?

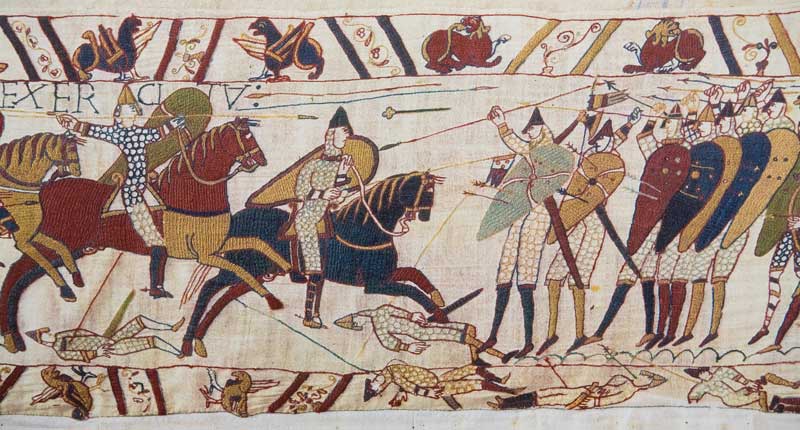

So who were the Normans, this new dynasty from northern France who came across the English Channel with such power and strength to conquer the Anglo-Saxon army of Edward the Confessor’s chosen successor, King Harold?

Who were these Normans who so famously shot King Harold in the eye with an arrow at Hastings?

The Normans, a name in French that means Norsemen, were in fact recent descendants of the Vikings who had settled in north western France at the end of the 800s. They were traders and Crusaders, as well as warriors, and for 200 years they had ruled their patch of France close by to the French kings in Paris.

Often warring with their bigger neighbor, they fought for control of the castles that gave domination over the rich agricultural land that in turn gave control over the food supply.

Like so many warring clans going back to the time of the Bible and the birth of civilization and settled society in Ancient Mesopotamia, the Normans understood the physical control of this, the fields and the granaries, was at the very heart of their survival.

Over time, they had become more and more successful and, by the time that William inherited the duchy, they had come to rival the richest and most powerful of all Europe’s monarchs, including the Holy Roman Emperor himself.

So the Norman state that William the Conqueror was in charge of when he arrived on the Sussex coast in October 1066 was strong and confident, and William had clear plans for England after his coronation at the Confessor’s abbey church at Westminster in December 1066.

At the heart of this plan was the imposition of Feudalism and the replacement of the Anglo-Saxon aristocracy and theocracy, leaving England pretty much in the hands of the Norman elite that he had brought with him.

In all this, William chose to work closely with his half-brother, Odo, Bishop of Bayeux, who was later responsible for commissioning the Bayeux Tapestry.

As we have said, William was quick to bring in Norman nobles, administrators and clerics to run this new section of his Norman empire, and, in fact, he soon left to return to pressing business in Normandy, leaving instructions as he sailed back across the English Channel, returning only when he needed to lead his armies against rebellion.

Most notably this included the Harrying of the North in 1069-70 with the Domesday Book, written some 16 years later, still recording that many villages across the northern counties were ‘laid waste.’ Such was the shocking power and devastation of the occupying Norman force.

As we have said, at the heart of these plans was Feudalism that, in essence, demanded the domination of the Anglo-Saxon population, both high born and low. But given that the invading force never numbered more than some 10,000 Normans, help would be needed to achieve the subjugation demanded by the new king.

As a result, Odo ordered, on the new king’s instructions, a massive castle building programme, using the famous Norman motte and bailey plans that were so well copied in other parts of the world soon after.

These Norman castles were quickly built by masons and engineers brought in from Normandy, who worked on individual projects up and down the country under the watchful eye of the Master Mason. In general, there would be 2 types of masons who worked under him, the hewers, who carved the stones, and the layers, who placed the stones in to the building.

All of this, of course, was paid for by draconian taxes extracted from the local population. Taxes and tax collection, after all, lay at the heart of why the Domesday Book of 1086 was commissioned and why the surveyors sent out to every English town and village were ordered to be so thorough.

Of all the castles of England, the Tower of London, still perhaps London’s most iconic tourist attractions some 950 years later, is the most famous. Within a generation or so, 50 or so more Norman castles, such as the one in Kenilworth in Warwickshire, with its magnificent red sandstone keep, were to dot the English landscape.

Why did the Normans build cathedrals and churches?

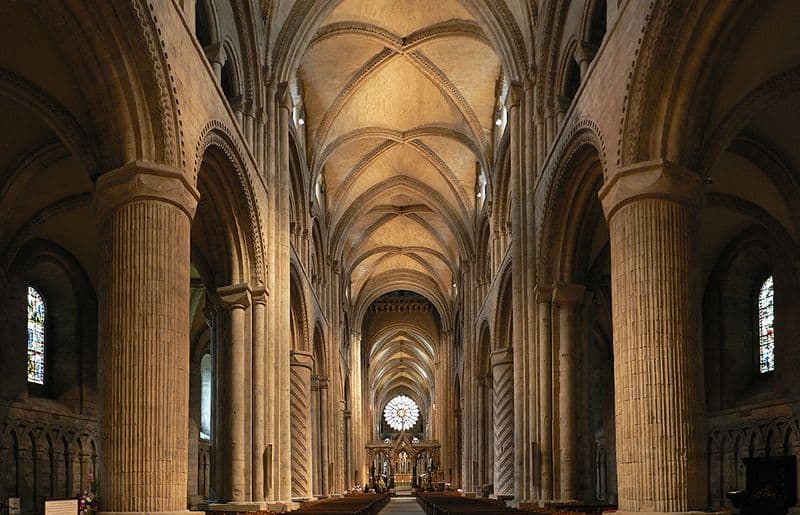

But alongside this huge Norman castle building programme, a huge mirror programme of cathedral building was also put in place, with 15 new Norman masterpieces put up in the next 90 years or so. Of these, 13 still remain, with only 2 lost to us: Old St Paul’s, burnt down in the Great Fire of London in 1666, and Old Sarum, soon replaced by Salisbury Cathedral, pulled down in the reign of Richard the Lionheart.

But the spiritual and political power over the population that came with the new cathedral building programme was supplemented by another one which, one could argue, was to have an even greater influence over the people of England.

This was the great Norman church building programme that, over the reigns of the 4 kings, saw some 7,000 new Norman stone churches built across the vanquished land, from north to south and from east to west, marking the landscape with new churches to fulfil both William’s political and religious ambitions.

Of these, perhaps a quarter or so remain to the present day, with many destroyed or renovated, often sadly vandalised beyond recognition in the Victorian period when the gothic style was in vogue.

So perhaps as many as 2,000 original Norman churches can be visited today, mostly continuing as working churches serving the parishes of the Church of England and other denominations, looking after communities up and down the country.

Working churches such as St Andrew’s near Salisbury in Wiltshire, or such as St Michael’s in Mickleham in Surrey, near London, a similarly beautiful Norman masterpiece. Or further north in Yorkshire, the site of the Harrying of the North, where we find the granite permanence of St Helen’s in Skipwith. The photographs of the three churches, below, are by Lionel Wall.

St Mary the Virgin, Iffley, Oxfordshire

St. Michael & All Angels, Copford, Essex

Church of St Mary and St David in Kilpeck, Herefordshire

Norman staircase at Canterbury Cathedral

Photos by Matthew Slade

St Mary the Virgin, Iffley, Oxfordshire, sits above the River Thames on what would have been in the 12th century a sprawling estate. In modern times, the sprawl of Oxford has engulfed the surrounding area.

The church was funded and built circa 1170 by the Norman lord Robert de St Remy and his wife, who was a member of the powerful and wealthy Clinton family.

Historians suspect that the Church of St Mary and St David in Kilpeck, Herefordshire, sits atop the ruins of a Saxon church. The church is known for its stone carvings, and is described by Pevsner Architectural Guides as one the most perfect of Norman churches.

Placed amid a woodland glade, St. Michael & All Angels church at the edge of Copford village in Essex offers visitors a close-up view of 12th-century wall paintings. Around 34 subjects are featured in the frescoes that cover all walls and vaulted surfaces. The murals are thought to be the work of a Master Hugo of Bury St Edmonds.

The Norman stone staircase at Canterbury Cathedral leads to the library of the King’s School. It’s said to be the only C12 staircase in England. The period of C12 Norman architecture featured specific moldings around such elements as arches.

What are the characteristics of Norman churches?

All show many of the unique styles and architectural peculiarities of the Normans: the half-round windows; the door and arcade arches; and the massive walls and cylindrical pillars. All these blended so that a Norman church is both massive, square and immovable while, at the same time, also seeming delicate with beautifully carved stone ornamentation.

At St Leonard’s in Romney, on the marches in Kent where Dickens’ wrote about Magwitch in the opening scenes of Great Expectations, we see an excellent example of this size and solidity manifested in the square tower, a noted trait of the Norman church.

It is not surprising, perhaps, given the closeness to violence and rebellion in which the Normans found themselves, that the square tower, guardable on 4 sides, was a shape that could be easily defended.

At St Leonard’s in Kent and at St Andrew’s in Wiltshire, we see another hugely popular characteristic of the Normans, and that is the wide, decorated semi-circular rounded arch. This is a device that is used with both doors and windows, and, in this regard, most Norman churches we see in England match their Romanesque cousins of the continent.

Surrounding the door was usually a zigzag or a chevron masonry decoration, called a moulding, that catches and raises the eye. On both windows and doors, this pattern usually stopped at the end of the semi-circular arch leaving a straight clean column to the ground.

At St Andrew’s, we see an exquisite arch at the end of the nave, with a beautiful semi-circular design surrounding it.

The arch at St Andrew’s sits below the even more impressive, though not Norman, Ladder of Salvation wall painting. Many of these were seen as blasphemous and destroyed during the Reformation of the 1540s, and only about 40 or so remain throughout the land.

In Romney, we can also see an excellent example of Norman architecture with a wide and rounded door at the entrance to the tower, while at the entrance door in Salisbury, our eyes are also drawn to the tympanum, an ornate triangular design above the door.

In Salisbury, the chevron was used to decorate the tympanum, but various other decorations were often also used, and these included all sorts of shapes, symbols and even animals.

St. Andrew’s, Salisbury (By Lionel Wall)

St. Andrew’s, Salisbury (By Lionel Wall)

Common bible stories were often, in an age of illiteracy, represented in church art and frescoes, and there is no better example of this than on the tympanum at the chapel in Aston Eyre in Shropshire.

Here, we see a classic wide arched Norman door, with a fantastic depiction of Jesus arriving at Jerusalem on a donkey, with one bearded character in front of him laying down palm leaves in his path.

Also, notice the exquisite Norman door, one of the oldest in existence.

A final lovely example comes from the north, from the county of Cumbria, the home of the Lake District, at St Bees Priory. Again we see a lovely wide and decorated Norman entrance door.

Free coloring page

Artist and fellow Steeple Chaser Serena Hackett has designed a Norman architecture coloring page exclusively for readers of Americana Steeples.

Sign up below for our weekly newsletter to receive an email with your free download.

Norman Towers, Doors, & Carvings

Photos by Matt Slade

The Church of St Kyneburgha in Cambridgeshire: Built on the site of a former palace courtyard that belonged to the second largest Roman building in England.

St. Andrew’s, South Lopham, Norfolk: The Norman central tower was added circa 1120.

Tewkesbury Abbey, Gloucestershire: Reputedly, the largest Norman tower in Europe.

St. Nicholas, Barfrestone, Kent

The central tympanum of the south doorway, circa 1180, has a figure of Christ in Majesty.

David, Kilpeck, Herefordshire

The central tympanum shows the Tree of Life with surrounding decoration including beakheads and green men.

Rochester Cathedral, Kent

The Great West Door substantially unaltered since the early 12th century.

St. Mary, Iffley, Oxfordshire

A carving of a king, reputedly Henry II.

St. David, Kilpeck, Herefordshire

A roof corbel of a dog and a rabbit.

Canterbury Cathedral, Kent

A column capital in the crypt, showing mythical beasts playing instruments.

Norman arches & columns

Another important characteristic of the Norman architecture was the size and the girth of the column, and these were generally both huge and cylindrical.

Many arches were often carved or decorated with flutes, spirals, chevrons, or other geometric patterns, although at Claverley this is not the case.

However, this is certainly the case in Surrey where, at St Nicholas’ in Compton, we see a beautiful pattern of decoration of the column capitals.

The capitals initially had a cushion appearance with the square block with rounded off lower ends, although later masons became more confident and theatrical in their use of designs.

All Saints at Claverley in Shropshire

Photo by Lionel Wall

St Nicholas in Compton

Photo by Lionel Wall

St. Michael and All Angels, Copford, Essex

The nave arcades. (Photo by Matthew Slade)

St. Peter, Tickencote, Rutland

The chancel arch. (Photo by Matthew Slade)

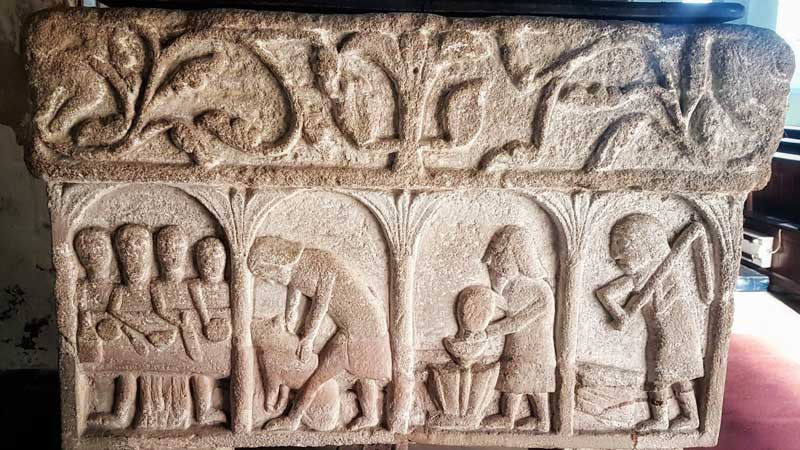

Norman fonts

Lastly, we must turn our attention to the font, which was a feature of all Norman churches. Many were removed during the Reformation and by other low church movements, over the centuries ending up in farms and the suchlike, but many remain that allow us to view and to study them.

Through this period, we can see a range of all shapes and designs being used, some quite plain and some carved with the most amazing collection of patterns and motifs.

Many were removed during the Reformation and by other low church movements, over the centuries ending up in farms and the suchlike, but many remain that allow us to view and to study them.

At Claverley, then, we very much see the former, a solid round block with carvings vertically down and around the font, while at St John’s in Crosscanonby in Cumbria, we see a far more complicated lattice design.

Finally, we travel to Warwickshire where at St Peter’s and St Paul’s at Colehill, we see extraordinary complexity and poignancy of design with the portrayal of the crucifixion.

St. John’s Crosscanonby Cumbria (Photo by Lionel Wall)

St. Peter and St. Paul, Colehill, Warwickshire font (Photo by Lionel Wall)

St. Mary, Eardisley, Herefordshire font depicting the Harrowing of Hell. (Photo by Matthew Slade)

Norman font at Burnham Deepdale, Norfolk (Photo by Matthew Slade)

Our tour of Norman churches comes to an end

So now we must end our ramble across England and the Norman churches that still, after nearly a millennium, pepper our rolling landscape. Norman churches make up a hugely important section of our parish churches network, and they are a part of a live and vivid historical heritage that shows us where we have been and from whence we have come.

But also, perhaps more important, a study of England’s Norman churches today shows us that our ancestors of 900 years ago were not so very different from ourselves, following them by some 40 generations removed.

We can see in these churches that the shared values, beliefs and hopes of those long departed worshippers bind us all in a common tapestry of birth, worship, and death – that is as old and as immemorial as the English landscape itself.

Meet the author, photographers, & artist

Andrew Hatcher was educated at East Anglia, Oxford, and York universities in England before embarking on a career in education that has taken him to posts in the Middle East, the Far East, Africa and England over the past 34 years. He has a particular interest in colonial and architectural history. He can be reached at [email protected].

He is the author of The Greatest Leap, a decade-by-decade history of the 20th century, published by Troubador in 2015, and available in the USA at amazon.com (ISBN-13: 978-1784621735).

Lionel Wall has a life-long amateur interest in church architecture and mediaeval history. In 2009 after a long career in corporate management he created a historical church website www.greatenglishchurches.co.uk as a retirement project which has, much to his own surprise, now been viewed by over two million people worldwide.

He brings to it a deliberately irreverent sense of humour and keen sense of the bizarre, which he sees as an antidote to the stuffy and narrow approach of most writers and academics.

Lionel feels strongly that you cannot fully understand mediaeval art and architecture without also understanding something of the religious, social, and political landscapes within which it was created and within which its creators had to survive. He has an especially keen interest in the Anglo-Saxon and Viking eras.

In 2012 he discovered a remarkable and hitherto overlooked mass of 15th century sculpted friezes in the East Midlands of England where he lives. In 2013 he self-published a book “Demon Carvers & Mooning Men” about them and a second edition is in preparation in which he will more fully explore them within the context of the mediaeval building “industry.” A synopsis of the work can be seen on his website.

Although he claims he is no great photographer, his pictures are in great demand from academics and students around the world. In 2014 some of his work on Anglo-Saxon churches was incorporated into the teaching materials for England’s school curriculum.

His motto is “The more I find out, the less I know”!

Matthew Slade, was born in Essex, England, and currently lives in Rochester, Kent. He’s been interested in church architecture and medieval history since he was a young boy. Much of Matt’s spare time is spent touring the English countryside photographing churches. Fortunately for us, we can follow along those journeys through his Instagram account: @matt.afc

Matthew Slade, was born in Essex, England, and currently lives in Rochester, Kent. He’s been interested in church architecture and medieval history since he was a young boy. Much of Matt’s spare time is spent touring the English countryside photographing churches. Fortunately for us, we can follow along those journeys through his Instagram account: @matt.afc

Serena Hackett, who designed our free coloring page, is a Graphic Design student at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. She has a passion for art, and her main areas of focus are drawing, illustrating, and digital design.

Enjoy more articles about church history

Surviving hard times in life as a church

When hard times in life happen, this traditional Methodist church found out that God can take them in surprising new…Read More

St John’s Episcopal Church

As soon as Connecticut settlers arrived in Worthington, Ohio, they unpacked and held a church service. Ohio churches were an…Read More

Historic New Orleans

In historic New Orleans, a city overflowing with culture and history, the old churches offer awe-inspiring architectural encounters.Read More

Roofless church

Unity and harmony beckon to us at the New Harmony Roofless Church, a modernist architectural masterpiece designed by renowned architect…Read More

The little white church of Fort Meade

The little white church of Fort Meade, Florida, has been an inspirational and historical landmark for 133 years and remains…Read More

Wendish heritage in Texas

A Texas photographer and historian recounts two journeys – the one that changed his life and the historical journey that…Read More

Teresa Trumbly Lamsam, Ph.D., is an accomplished Social Scientist and Journalist. Passionate about establishing credibility in the digital realm, she champions transparent and trustworthy online content. She is dedicated to producing content that sparks curiosity and nourishes the heart and mind.

I love old church buildings! The details, the artistry, the architecture- it amazes me what they were able to create, how much it stood the test of time without the use of modern equipment/tools.

I was blown away with how much I learned about Norman churches! I am pretty new to learning about architecture, and I love how you broke down what defines Norman architecture with all of the examples of the churches. So fascinating! I just printed the coloring page now too 🙂

Thank you for sharing so much incredible history and beautiful pictures. You do alot of research and it shows. Thank you for enlightening us with this beautiful post sweet sister … ❤

Hi! Thank you so much for this beautifully written and in-depth look at Norman Churches. Every photo included here tells a story!

Wow, you put soooo much information in this post! I loved looking at all the pictures as well.

That was quite the history lesson! Love it! It is interesting that the construction of these Norman churches was intertwined with the violent history that was common at that time. The churches are beautiful though! I am curious–were the churches built solely out of religious obligations by the Normans or was it part of a plan to use them to keep the populations under control? Or maybe a little bit of both.

Hi Linda. I’m Lionel who supplied some of the pictures. The answer to your question is – “both” – and more. The Normans first built castles to keep us poor old Anglo-Saxons in check. They were, however, “good Christians” and it is worth remembering that William got approval from the Pope before invading. So they then set about building churches – and bear in mind that most villages in England at that time were timber and thatch – having first replaced every bishop bar one. That also was part of a what we would now call a “shock and awe” strategy. Certainly, however, lordly prestige would have played a major part. William gave most of England to his knights and lords and they became pretty rich. What better way to show both your piety and your wealth than by building churches and endowing abbeys? It was pretty good for the future of your immortal soul too when you probably had quite a lot of sins to answer for when you met St Peter! At that time churches were owned by the lord, not by some nebulous organisation we would call “The Church”. That is why many (although not all) churches were listed in the Domesday survey. They were assets that the Normans could tax. Hope that helps.

Your post on Norman Churches is so indepth at portraying the history. I simply adore churches and castles and would love to visit every castle and church in the UK. Maybe one day ?

This is such a detailed and insightful post on Norman churches. Learnt so much, thanks for sharing.

I had no idea Norman churches were so interesting. This was so expansive!

Very interesting. I love to see the old architecture. So beautiful. Blessings, Joni

I loved the detailed information about Norman churches. I was fascinated by the intricacies of the doors and the pillars. Thank you for sharing your knowledge about Norman churches.

Wow! This is quite fascinating. I never heard or have seen Norman churches. Such a rich history and the architecture is incredible!

Wow! This post was so informative and taught me so much. And the pictures were simply beautiful! Thanks so much for taking the time to write this!

Loved this post with all the beautiful pictures of Norman churches! Especially the doors! I enjoy thinking about old buildings and the stories they could tell. Very informative post, thank you!

The photos of the Norman churches were so interesting to me. They were so grand and had so much detail!

A very informative article on the Norman churches in England. I have been to England one time but this article and the beautiful pictures inspire me to return with new eyes!

The detail and intricacies of these ancient buildings is truly amazing. To think it was all done with hand tools and man-power rather than electric machines and equipment.

Before reading this article I had very little knowledge of the Norman history and their influence on religion, culture and architecture. Very thorough and lovely photos!

Wow! Another lesson in history of Norman churches, thanks for sharing.

These Norman churches are beautiful and even more intriguing knowing the history. I especially love the rounded window architecture!

Such beautiful pictures of these oustanding buildings. I’ve always wanted to go to England to see some the history.

I no ideas about the background of the Norman churches.

Such a fascinating read! I had no idea that the Normans were descended from the Vikings… what a cool link.

And it’s also great to learn about the Norman Churches and Castles. I had no idea the Normans did so much of that building. As conquering as they were, they left behind some beautiful architecture!

I love learning and especially about church history and architecture.

Wow! Love this so much! So beautifully & knowledgeably written. I feel like I’ve been to a wonderful, huge meal & have come away very satisfied! Thank you!

That’s so awesome to hear! Thank you! I thought the team really pulled off a good one with this!

Great historical article. Particularly since I had the opportunity to spend time in East Sussex and Kent counties. Traveling up the coast from Hastings in E. Sussex to Folkestone, Dover , and Ramsgate in Kent. Also throughout Kent and East Sussex heard a lot of history and the year 1066 is like memorable years to Americans (1492, 1776, 1812). The article brings back a lot of memories.

Such an interesting reading. Awesome information and photos. I have culture shock. I would like to visit these places one day. Thanks for sharing!

Same here, Rick. I really hope to visit in person to see these churches and so much more!